A commonly used rule of thumb is to buy a knife that is somewhere between three and five times as thick as the thickest material you plan on slitting because a rotary knife has to be able to withstand the most challenging job for which it might be used.

For example, if you are going to cut material up to 0.187 inches thick, you will need a knife that is between 0.561 inches (about 3 times) and 0.935 inches (about 5 times) thick. More commonly, these sizes shrink to 0.500 inches (about 1.2 cm) or even 0.750 inches (about 1.9 cm). (In reality, few people use a 0.750-inch knife, and even fewer people choose a 0.935-inch-thick knife to cut 0.187-inch steel.)

These rules of thumb have been debated for years, and which one to use depends on who you talk to. A blade three times thick is adequate for thinner cuts and is cheaper, but is not rigid enough for thicker cuts.

A blade five times the thickness of the thickest material will provide better rigidity, but it seems to be overkill for most products to be cut. Most service centers are unwilling to spend money on a 0.750-inch-thick blade because a 0.500-inch-thick blade is usually sufficient.

The popular choice in this situation is to buy the 0.500-inch-thick knife. Some choose this thinner knife to save money. Others choose it because working with the 0.500-inch-thick blade simplifies setup math, and blades can be doubled up if needed.

Often, service centers buy the same knives that previously were used, which seems to make sense if they didn’t experience any problems. Unfortunately, slitting line personnel don’t always realize that a particular problem was caused by a knife that was too thin.

The Problem of Deflection

Using knives that are too thin can be the root of two major quality concerns. First, when knives deflect, they can change the width of the strip–so much so that the knife deflection could cause the strip to be over or under its required finished width, resulting in the setup having to be remade or material being scrapped. The deflection can have an inconsistent, to-and-fro action, giving the strip a serpentine shape when measured with micrometers.

Not only do rotary knives deflect inconsistently, they do not deflect the same amount, depending on their position on the arbor. Knives that are in the center are figuratively trapped, in that the forces working on them from the top, bottom, and either side are relatively even–the knives are in check, so to speak. Knives on the ends of the setup cutting the trim do not have an opposing force working on them from another cut. These knives are allowed to deflect toward the outside of the machine without any recourse, and they can deflect enough that the trim cut stops slitting.

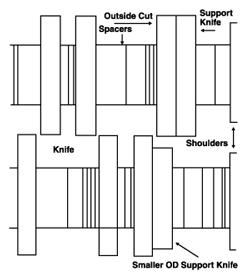

Note: If losing the trim cut is your biggest problem, double up the knives on the outside cuts.

Figure 1 illustrates how this can be done on a male cut by putting an additional knife on the inside of the cut (if the mult width allows room for this).

Figure 1

But what do you do if you are slitting a strip so narrow that it does not allow for an additional knife inside the cut? The easiest solution is to reduce the outside diameter (OD) of either an existing knife or, better yet, an old scrap knife at least 0.500 inch under the OD of the working knives. Put this knife on the outside of the cut as illustrated in Figure 2.

This is not as effective as the additional knife used in Figure 1 because of the way the knife deflects, but it can help if no alternative is available.

The second quality concern when using too-thin knives is that the knife deflection can induce camber into the slit mult. On narrow mults, typically less than 2.000 inches wide, a different clearance resulting from knife deflection on either side of the mult can cause the material to camber when it comes out of the slitter head.

Figure 2

Figure 2

Reducing Deflection

The available solutions for reducing knife deflection are relatively simple. One way is to double up your knives. This means using two knives with the same OD, back-to-back. For example, if you’re using 0.500-inch-thick knives, put two together to form a 1.00-inch-thick knife. Some of the better shimless software programs allow you to enter additional knife sizes as needed, which makes this an easy fix.

Typically, two 0.500-inch-thick knives are not considered equivalent to one 1.000-inch-thick knife. Because of the potential for slippage between the surfaces of the knives, you should give the two knives a 25 percent reduction in apparent thickness. In other words, two 0.500-inch-thick knives are equal to one solid 0.750-inch-thick knife, and two 0.250-inch-thick knives are equal to one solid 0.375-inch-thick knife.

A less desirable but equally effective way to reduce knife deflection is to reduce the OD of the knives. This typically is a last resort because of the expense of grinding down the OD of the knives and the rubbers, as well as the lost knife life.

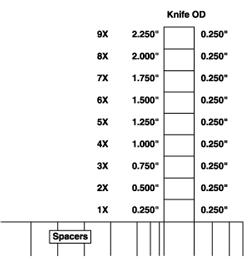

One obvious answer would be to buy thicker knives, but how thick should they be? If you are slitting narrow mults (less than 2.000 inches wide), there are additional considerations because it is much easier to induce camber into a slit mult that is less than 2.000 inches wide. Figure 3illustrates how thick a knife needs to be in relation to the height of the knife over the spacer if you are slitting narrow mults. This is one aspect of knife buying that typically is overlooked.

You may face more problems if you are purchasing replacement knives but were not around when the existing knives were new. If you never experienced the knives when they were new on the machine, you might not be aware of the potential deflection issues. If you are fortunate enough to have a setup person who has been around since the machine was installed, or at least when the knives were new, that person probably will tell you that there were a lot more camber problems when the knives were new than there are today. As the knives get ground down, their camber problems dissipate.

Most of the slitting lines made these days have about 1.500 inches of knife protruding beyond the spacer. The slitting lines made 10 or more years ago usually had knives with 1.750 to 2.000 inches of knife protruding beyond the spacer OD. A knife that was too tall often was the source of knife deflection problems.

Knife deflection is a function not only of the thickness of the knife but the height of the knife relative to the OD of the spacers (the knife’s main source of support). You always can resort to the 5xrule, but sometimes this will not be adequate when slitting narrow mults. In some instances, a knife that is 7-1/2 times thicker than the material still is not sufficient to resist the forces acting on it.

Another practice is to dedicate your older, smaller-OD knives to slitting the narrow-mult jobs. Use your new knives for slitting wider materials, on which it is much more difficult to induce camber into the strip.

Figure 3

Figure 3

Conclusion

In coil slitting, typically thousands of pounds of separating force are acting on every cut. These separating forces that are generated are determined by the knife diameter, the thickness and hardness of the material being slit, and the amount of vertical knife penetration. All of these factors have a bearing on the amount of knife deflection, arbor deflection, horizontal knife displacement, and, in the end, the quality of the finished mult.

While you’ll never eliminate all of these deflections completely, your goal should be to minimize these effects to reduce other stresses on the knives and the material while slitting.

No Comment

You can post first response comment.